UNLOCKED, Vestibules, Bristol City Hall. Feb 20-24, 10am-3pm.

UNLOCKED, Vestibules, Bristol City Hall. Feb 20-24, 10am-3pm.

We had a fabulous open event, a incredible turn out despite the torrential rain outside. Thank you to everyone who came along tonight and giving us such deep and heart felt comments.

alldaybreakfast – UNLOCKED opening event, 17 November 2016 from alldaybreakfast on Vimeo.

We put on a picnic lunch in the museum so that people could enjoy the experience of looking at the collection and share their memories of what is was like to work in Stoke Park, Cosham, Hanham and Glenside Hospitals from the 50’s onwards.

Fewer people attended than we had hoped due to illness and bad weather. However, the discussions that took place were probably more intimate because of this. It was very moving to be given an insight into how it felt to work in both Stoke Park and Glenside hospitals.

One example of the depth of the experiences that were shared moved us all to tears. Mrs. D, was recruited in Jamaica at the age of 19 to work in Stoke Park Hospital, she told us of her experiences when she arrived in Bristol and went to work. She described herself as having been treated like a princess by her mother “My hands had never touched dirt”.

She went to be interviewed at Stoke Park at 9am in the morning and was given the job straight away. She was expected to begin work at ten that same day, provided with a uniform and ‘given’ a Ward to look after without supervision or training. Mrs D told us of the shock, horror and disgust she felt on seeing the profoundly disabled children. Mrs. D was very honest about her feelings. She had had no idea that “such people could live”. She talked about crying herself to sleep for “three months solid”. When asked how long she had endured it Mrs D replied “44 years”. Asked, what had kept her going back day after day she responded quizzically, “Love, of course, love kept me going. I knew that the children would suffer from the loss of me, would miss me, and thought that they had enough to endure.” There were nods and mutters of agreement from the other participants and not a dry eye in the house.

We plan follow up sessions with The Golden Agers because there is a wealth of material about the experiences of Caribbean nurses who worked in these hospitals that it bears further investigation. Ideally, we would like to collect stories, experiences and artefacts and make a permanent display in the museum to reflect the contribution made by Caribbean Nurses. We intend to fund raise separately for this project.

Pat Jamieson, 16/11/2016

This exhibition marks the halfway point of alldaybreakfasts’s time as artists-in-residence at the Glenside Museum, drawing together work the each artist has developed. The aim of residency is to explore the Museum’s collection, to unlock the history of the objects and their associations and to give voice to the anonymous patient. In the work, myths and common perceptions of the institution are challenged as is the tension between the original meaning of ‘Asylum’ as safety and it s transformation to imply incarceration. Emotions and the language surrounding emotions are explored, where and how they are experienced in the body. And the relationship between masculinity and mental health is examined.

The work, by Tommy Cha, Anwyl Cooper-Willis, Pat Jamieson and Carol Laidler, includes video, installation, poetry, photography and drawing, and aims to stimulate new conversations around vitally important topics related to the human mind through art.

alldaybreakfast have been staging site responsive exhibitions and participatory art events since 2012 and were awarded funding by Bristol Creative Seed and the Arts Council for their time as artists-in-residence at Glenside Hospital Museum, one of only three Lunatic Asylum Museums in England.

12 – 27 November, Tuesday – Satruday 12.00 – 15.00

Opening event on Thursday 17 November, 18.00 – 20.30.

An now we are stating the hang. Very exciting to see work coming together and starting to turn into something real and coherent.

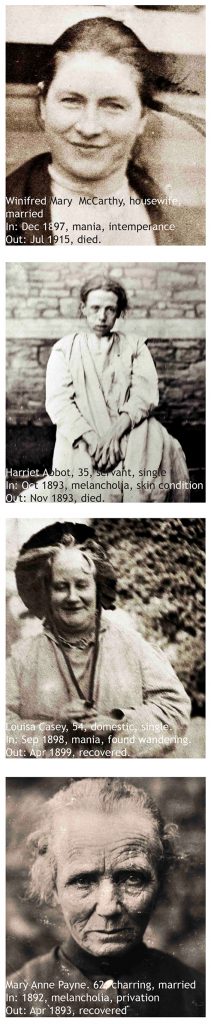

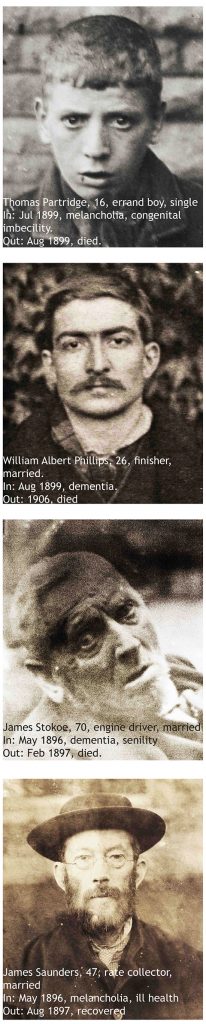

A book made with portraits of patients at the hospital in the 1890s

A picture of our exhibition and studio space in The Unit in the Arcade, Bristol, which we’ll be occupying throughout November. We moved in on Monday 31 October and are currently making and hanging some of our works, inspired and created during our residency in Glenside Museum. The exhibition is opening next weekend, 12 November, so lots to do and organise!! This exhibition is the halfway point of our residency, giving us time to experiment and select works that will go into an installation in the Museum in February 2017. Everyone in alldaybreakfast is feeling both excited and nervous right now!

Boy’s Don’t Cry Event, 1st/8th October 2016

I’ve hosted a men only event, split over two dates in the Museum. Each event was 2 hours… where we talked, questioned, exchanged experiences, debated and ate cake.

I want to say thank you to Paul and Viv, (two retired male psychiatric nurses who worked at Glenside) for sharing their experiences working in the hospital and providing us with an insight into what patients lives were like in the hospital.

I also want to thank the ten men who took part in the event. Here’s a selection quotes from event, in no particular order:

“how can anyone have time to contemplate with all the noise and distractions around us”

“Do you really believe there is someone in control!”

“People are susceptible”

“People go to doctors expecting an answer”

“Schools don’t teach the things we need to learn, like money”

“It would be useful to know what we are trying to do and to get out of this”

“I realised having two sons myself, I’ve become like my parents, telling them to go outside, play football, enjoy the sunshine… they come home, play games… they only talk to me, when there’s a problem with the computer”

“People are stupid”

“We are dealing with conflict, internally”

“It’s simple, turn it off!”

“How can you assume everyone is like that, you don’t know anything about me!”

“It’s complex”

“Life is simple really, we just make it complicated.”

“I’m feed up with seeing violence, blood and gore on tv, why do they have to constantly repeat it over and over… I’m complete desensitised to it, I can’t care anymore”

“There’s a reason we are made to feel incapable”

“I fully respect what you say, but…”

“You can choose to ignore TV!” “I have stopped watching TV, I watch YouTube and alternative media.”

“You can make your own choices”

“Nhs should use talking therapy” – “Nhs does use talking therapy”

“We’ve got to the end and haven’t talked about mental illness!”

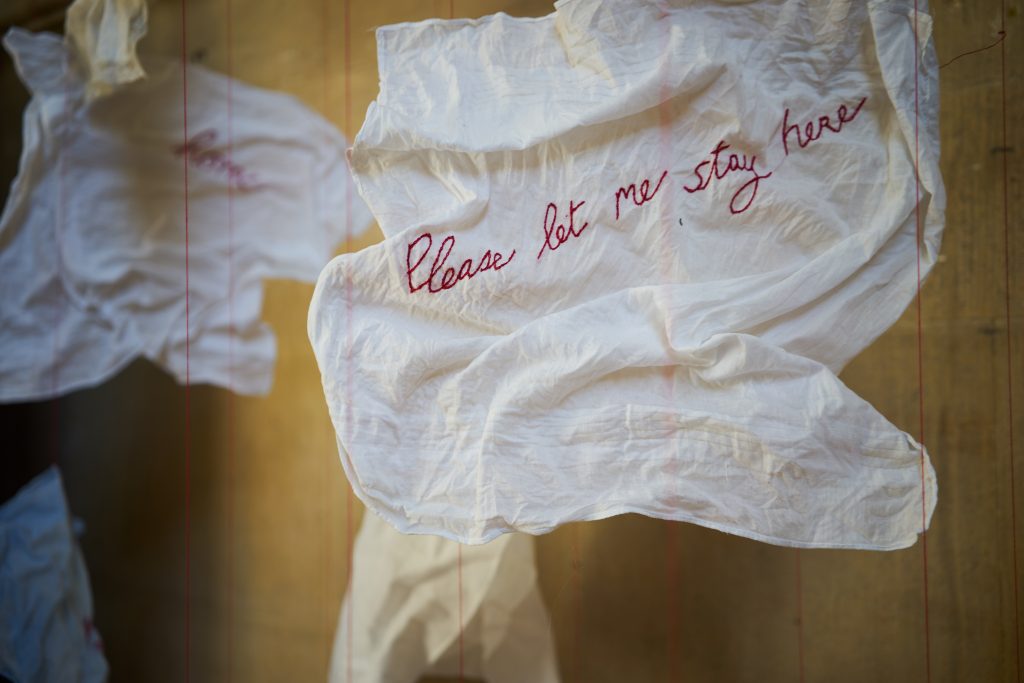

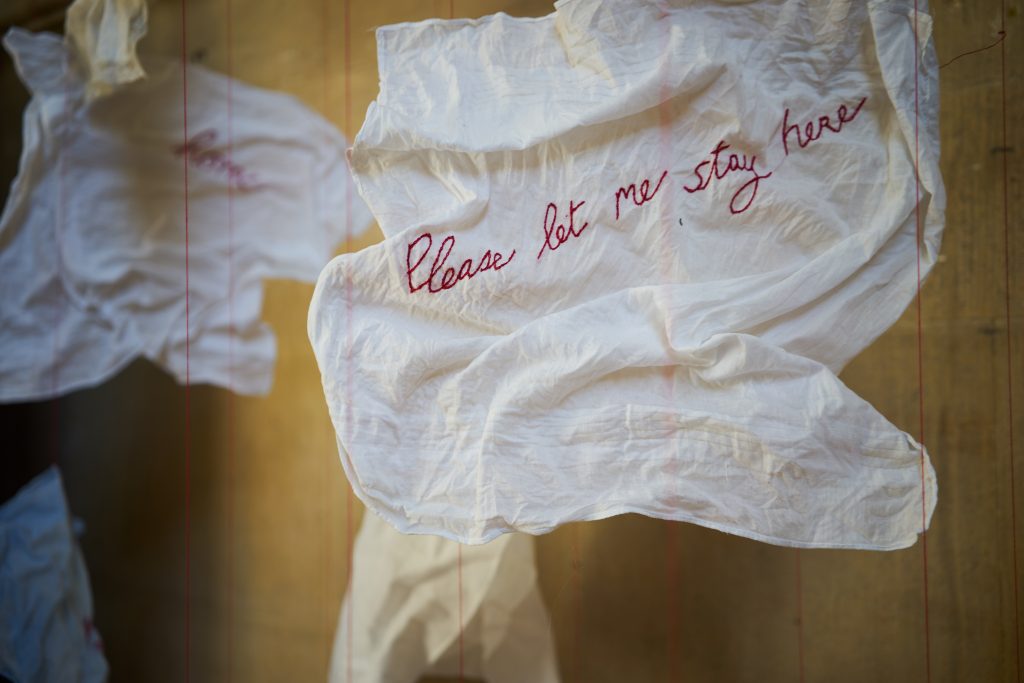

The silk rags are a graph to show women admitted to the asylum over the same period, 1861 – 1900, each one represents ten women.

Women admitted are separated into single married and widowed, from left to right in the photo. The red rags show women for whom childbirth or specifically female related problems were indicated as a contributing factor to their admissions. The graph shows about 1000 each single and married women and somewhat over 300 widows. The widows have very few female problems, perhaps due to being mostly older. The single women also have very few of such problems and married women many more, as can be seen form the photo. One might expect that ‘hysteria’ would be a common reason for admitting women to the asylum, but there are only about five mentions of the word, of which four relate to single women.

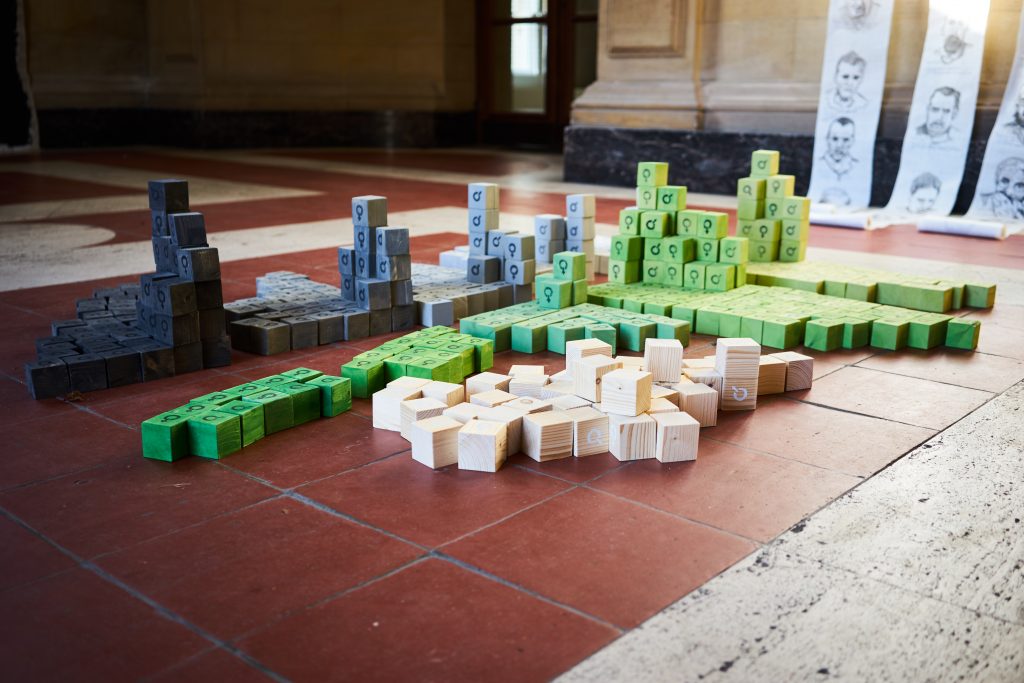

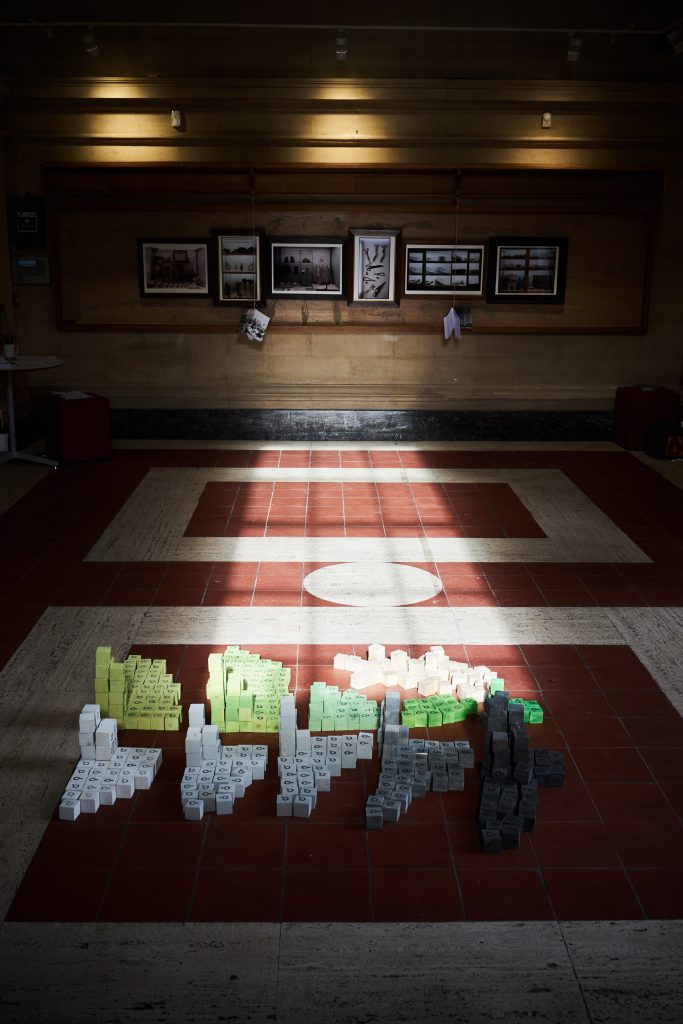

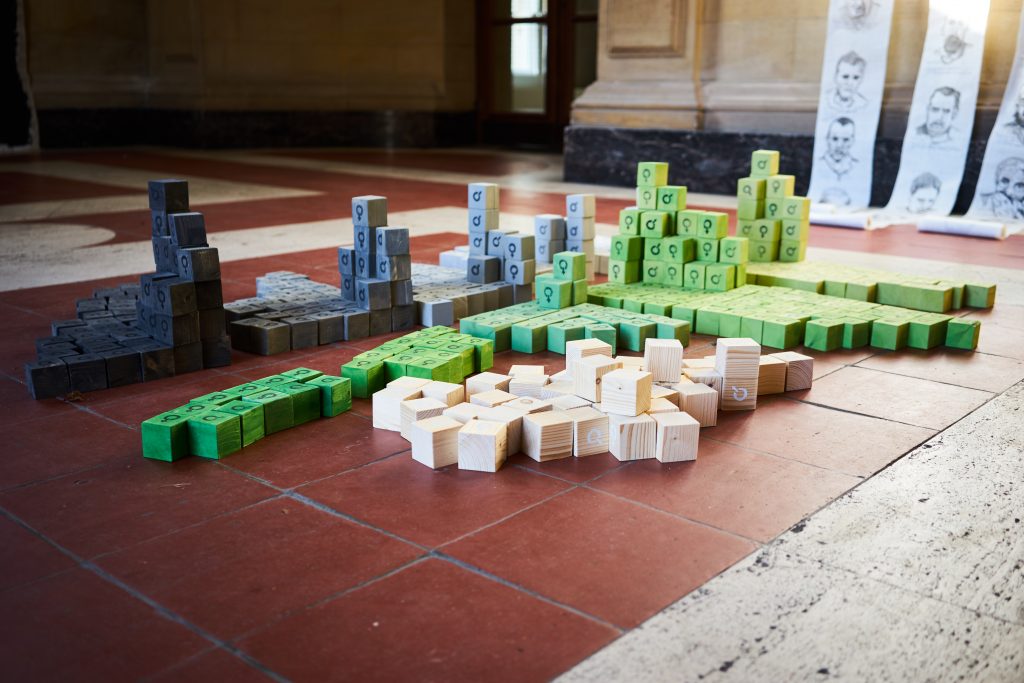

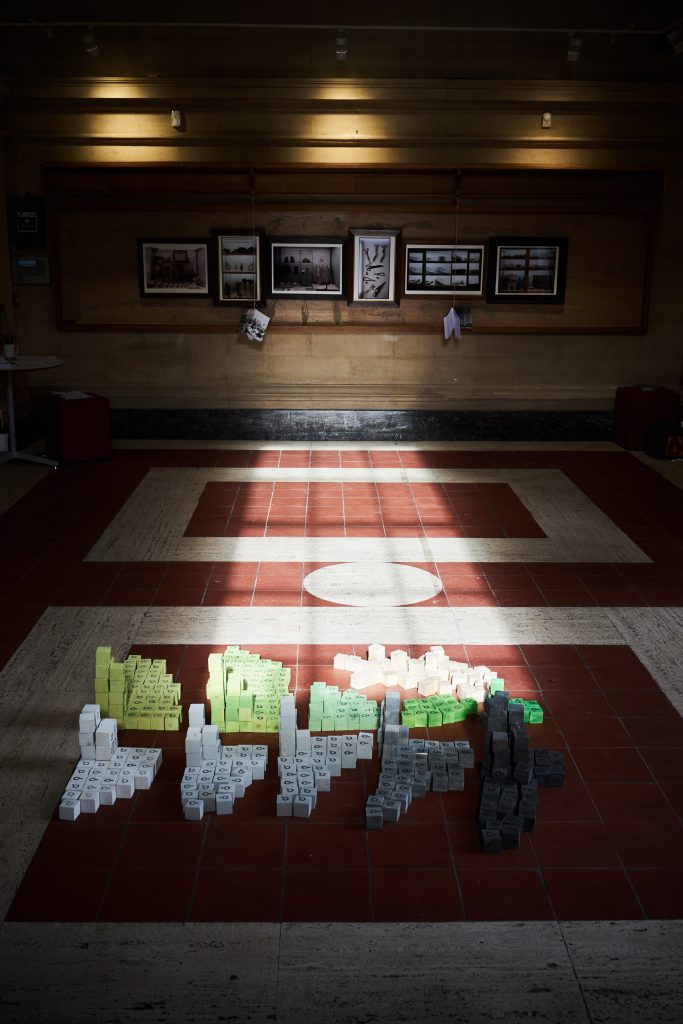

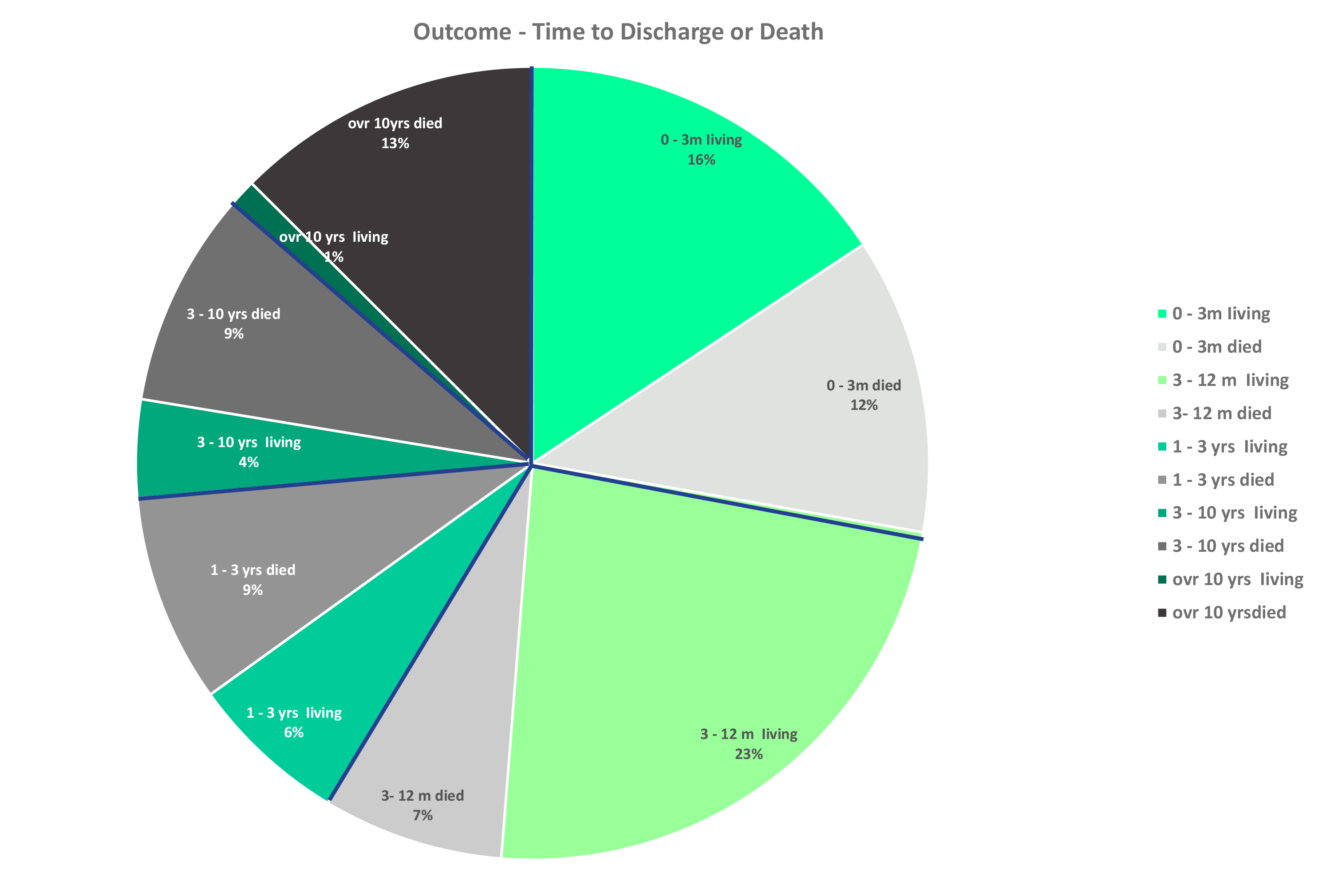

The blocks are a three dimensional graph, an attempt to bring thoughts about the patients into the museum. The legalities of confidentiality are such that only data over 100 years old can be looked at without permission of the patient or their family. So the central reason for the existence of the asylum is little in evidence in the museum.

Their aim is to start discussions about the outcomes for patients admitted to the asylum in C19th through the numbers represented in the graph. The blocks were shown at Glenside Hospital Museum’s Bristol Doors Open 11 October, 2016. A large gazebo was set up for alldaybreakfast by the front door on this beautiful autumn day.

Each block represents ten men or women and is labeled by gender and coloured, green for patients who left on their own feet, ‘restored’ or ‘relieved’, grey for those who died in the asylum. The darker the colour the longer the person was in the asylum. The unpainted blocks at the far end of the table represent people who did not have a clear outcome; they were transferred to other institutions or no outcome is recorded, or they escaped! Thirteen men and one woman are given as ‘escaped’ during the 38 years covered in my study.

Just looking down the table it is clear that the largest cohort is that of people who left between three months and a year of admission, beyond a year’s stay the numbers fall off quite sharply. Of those who died many did so in the first year. Most of those who stayed in the asylum for over ten years died there.

The blocks show that within the first year of being admitted, over half the patients left, but a significant proportion of those people left ‘feet first’. Just under half of the admissions were in for longer than a year. About 70% of people who left alive, left within a year, and about half of the people who died in the asylum died within their first year.

Overall during this time there were slightly fewer women than men admitted but men were more likely to die (perhaps they were more unwell on admission) and were more frequently diagnosed as suffering from ‘General Paralysis of the Insane’. Now know to be tertiary syphilis and fatal within about three years

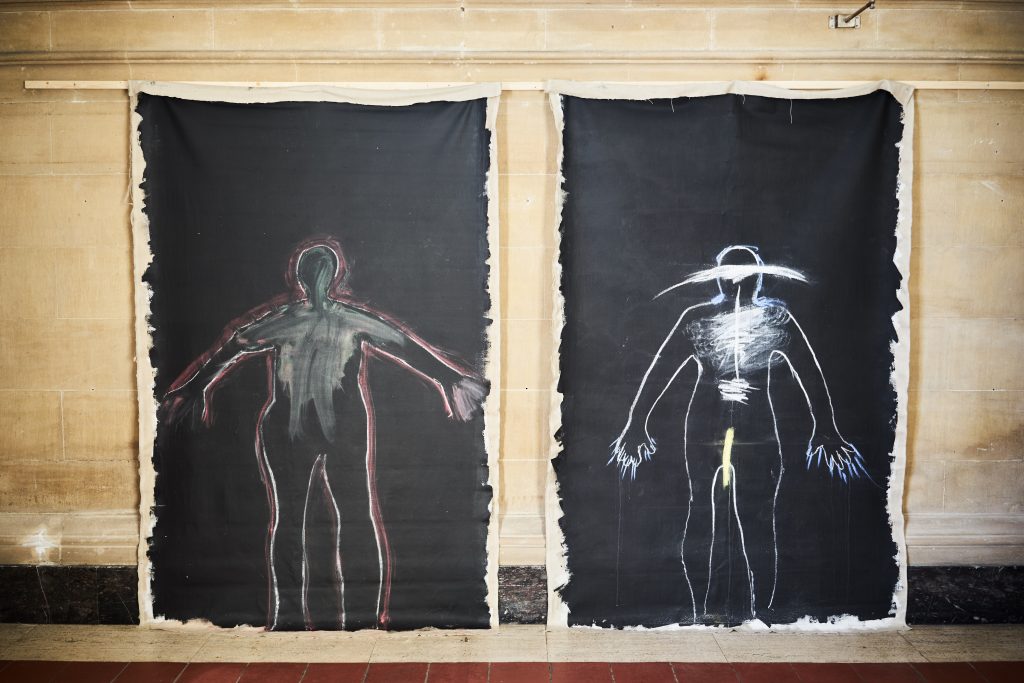

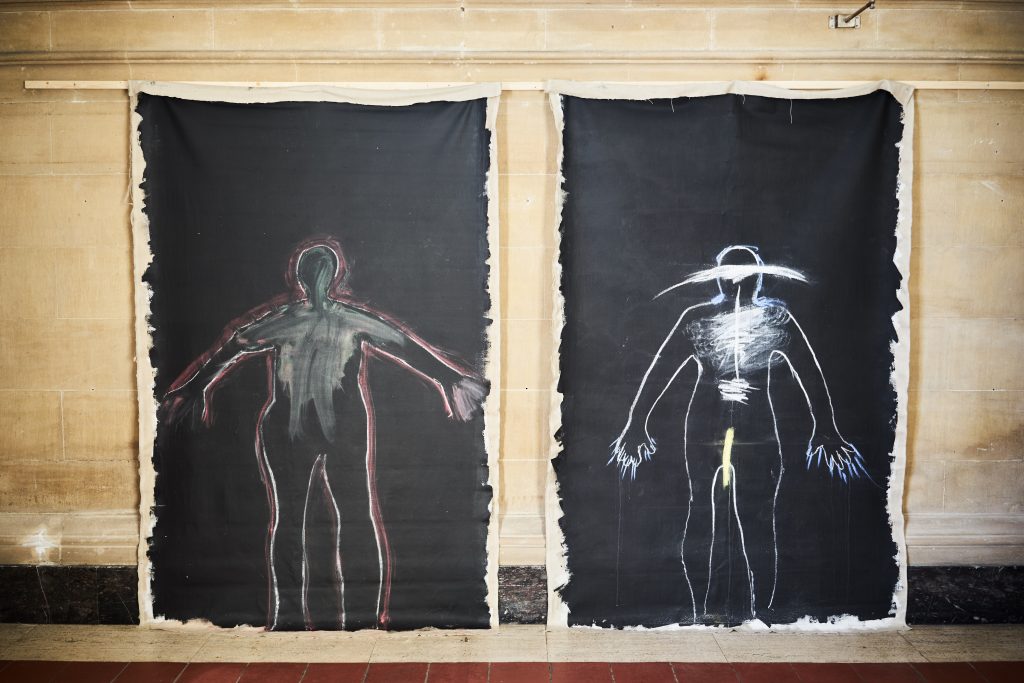

Heritage Open Doors Weekend, September 10th – Naming of Parts – Pat Jamieson and Carol Laidler

For the Heritage Open Doors Weekend, September 10th we ran a participatory event as part of our research for Naming of Parts. We set up an awning outside the Museum and placed a table with crayons, chalks, pencils and small silhouettes of figures to label and colour, as well as two life-size blackboards leaning against the Museum. We wanted to work with visitors to examine emotions, where they are held in the body, how they are labelled and how they are experienced and use this to open up conversations about how it feels to be alive.

We asked people to shut their eyes for a minute and be aware of where they felt physical sensations in the body and then describe these sensations by writing or drawing.

This process allowed us to enter into a conversation with participants about complex feelings. We were interested in engaging people in thinking about how language is used in relation to how we experience a range of complex responses to the world outside ourselves as well as our own physical reactions. We wanted to find out if people felt that there were feelings or emotions that existed and were experienced in our bodies that did not have a name.

The event was a great success. Despite the rain we had a steady stream of visitors, upward of two hundred, many of whom were interested in taking part. In fact there were times when it was hard work keeping up with demand.

The event was both challenging and intimate and we were surprised and moved by the quality and frankness of the people who took part. Of particular note was a family of four, father, mother, teenage daughter and ten year old son with special needs, who engaged in the task with serious concentration and produced thoughtful images and insightful responses. Indeed we were overwhelmed by people’s willingness to work with us on what seemed like a very deep level. By the end of the day we felt that something very special had taken place.

Looking at my graphs and numbers I wanted to think how the humanity of the patients could be made more easily appreciated. Graphs are always a bit flat, and don’t convey so much if one is not used to thinking in those sorts of terms. But on the other hand how can one think about desperate people in such huge numbers. There are about 700 patient photographs all from the 1890s and looking through them is such a moving experience. Here are people who are just people who have somehow got to the point of needing serious help with getting on with their lives. We have no images of people admitted before about 1894.

I started thinking about bringing the graphs into the real world, tried piling up some lovely antique slate blocks I have (they had to be confiscated from actual children as they started throwing them round the room).

Then it occurred to me that if the blocks were coded somehow they would embody the graph and however they were arranged they would express what the graph was showing. So on to painted wooden blocks, with each block representing ten patients.

Green seemed like a nice, living colour so green is for patients who left, statedly recovered or relieved (their condition was improved), on their own two feet. The darker the colour the longer the stay. The blocks in the lower right corner are patients who left after more than ten years. A few people left who’s condition was said to be unchanged, others were transferred to another asylum, a few left with no outcome recorded and about eleven people (one woman and ten men) escaped at different times, these people are represented by plain, unpainted blocks. About half of the people admitted died in the asylum, these are represented by grey blocks which get darker for longer spent in the asylum, black for over ten years.

This photo shows people who were in the asylum for three months or less and people who died in the asylum within three months, within a year and within three years – three tones of grey.

The blocks show that about 70% of people who walked out did so within a year. Outcomes for men and women were different so I have marked the blocks with a gender.

The blocks in the background are unpainted. The painted ones have been stencilled with a gender. There seem to be a lot of women, but the men have fallen over!

I have made a huge number of blocks – two crates full! I want to invite people to arrange the blocks however they feel is good for them and to use them to gain insight into what the numbers are saying about the people passing through the asylum. There was very little to be done in the way of a ‘cure’ but rest and a plentiful and good diet probably helped quite a lot. Capable patients were given jobs helping out around the place. It was run as a community and had animals and market gardens where food was produced as well as a sewing room, laundry and kitchen where women were allowed to work. Both men and women helped out on the wards as well.

That so many people left in a comparatively short time suggests to me that the asylum did provide a genuine respite for patients from their very hard lives. The high number of deaths shortly after admission indicates very poor health at admission. GPI or general paralysis of the insane, what we now know as tertiary syphilis, was incurable before antibiotics which were not generally available until after the Second World War. Syphilitics would probably die within three years so I chose that as a threshold point.

This project is to be unveiled at the Glenside Hospital Museum for Bristol Doors Open day, Sunday 11 September 2016 so it will be interesting to see what comes out of visitors responses to these masses of blocks.

August 6th

We are well prepared for the first Unlocked Writing Workshop. Pat and I have made cakes and we’ve written copious notes. Anwyl brings strawberries. We sit round the large oak table usually weighed down with books below the photos of Victorian patients. There are ten of us – several volunteers from the museum itself and some artists new to the museum, an interesting mix. Pat and I have put together a series of exercises, some short and punchy to get things going and some longer with more time to observe, describe and reflect. One thing that strikes me when we share what we have written is that hearing everyone’s written descriptions of the cabinets is as exciting as looking at the artefacts themselves, sometimes more so. Something profound happens in the translation from looking to word. We write, read out and discuss. We had wanted to consider and talk about the assumptions that we bring to the place and at times the volunteers explain the background to contextualise some of the objects and photos that we’ve been looking at. Everyone here has brought their own histories and associations as well their own different writing styles. We collaborate to write a poem, each writing a line and then playing with the order to see what comes out.

Allowing myself the luxury of space travel

Colours shining, shimmering on white paper

Irrational thoughts

Out of darkness comes forth sweetness

Can it?

The organ sleeps

Its echoing voice silent

In the dim light

The patient act

Of being a patient

Held involuntarily

Stored in a cool dark place

There is so much noise here

The blast and tremor of the organ

Here are the keys to understanding

First stop to unlock

Sorry

We seem to have arrived in the wrong section

“….. it is still the case that the type of men we think die by suicide are the unwell, the disturbed, the unlucky; who stumble at life’s biggest hurdles and are too weak to get back up. Most of us like to think we’re made of sterner stuff. We don’t know that 75 per cent of people who take their own lives have never been diagnosed with a mental health problem, or that only five per cent of people who do suffer from depression go on to take their own lives.” extract from Britain’s Male Suicide Crisis by Sam Parker, published in Esquire UK, Dec 2015

“…. a more effective approach, argues Seager, is to help men adapt and evolve in a way that broadens the definition of masculinity, so that facing emotional pain, for example, is seen as a sign of masculine strength.” extract from ONS suicide statistics: 10 ways we can stop men killing themselves by Glen Poole, published in The Telegraph, Feb 2016

“… the stigma and taboo surrounding mental illness is still a huge problem, with a recent CALM (Campaign Against Living Miserably) survey finding that many men stay silent about their problems because they felt ashamed and didn’t want to talk about their feelings or make a fuss.” extract from Male suicide is a public health crisis… by Jack McKenna for The Independent, Nov 2015

16th July

When Pat and I arrive, Stella asks if we would like to work in the Turret Room. She unlocks the tower door on the outside of the building and we follow her up the narrow winding stairs into the balcony space above the children’s corner. Lit by a dusty window, the balcony is furnished with a metal filing cabinet, a large oak table and a shop manikin in a long navy dress and a wig. We sit at the table and look across to the organ where the organist, flanked by two large artificial plants on stands, sits playing “Has anybody seen my girl?” He pauses for a bite of biscuit and a sip of tea then plays on.

Up here we are struck by the cacophony of sounds that float upwards, the strange echoes that bounce around magnifying some tones more than others in this ear-like funnel; Fragments of conversations, hurdy gurdy chatterings, lively interlocutions, hard, happy noises. Across the nave the stained glass windows hover, more present up here. The only bright colour, animated light, stories etched unknown or forgotten in my secular mind. As ever the pervasive smell of the church, creosote, or is it oak? So strong it lingers on my clothes long after I leave. We write for 15 minutes and then read to each other.

Excerpt from Stained:

Stained

as the dust

motes

float

as the sound of voices

stain the silence

where once

the dying and the damned

shuffled

Stained

like the bed sheets

soaked

The organ

pumps

and the sounds

stain

this monument

built

on a gamble

that the future

will be better

a land of hope and glory

(so the organ sings now)

13th July

We buy sandwiches, crisps and strawberries on our way to the Museum. Each of us has baked a cake and after a mornings research, we prepare lunch for the volunteers. The video screen is set up so that we can show our website, the trolley loaded with cake and sandwiches. We make the tea and put out the chairs. There is a good crowd and plenty to eat. We introduce Unlocked, explain why we are interested in the museum and to give an example of our approach and the kind of art we make, we talk a little about our last project – The Time Machine. We also speak about the individual artworks that we are making in response to the museum and the events that we are planning over the next months: the Writing Workshop on the 6th August, the Memory Workshop we would like to run with the volunteers in September, the Boys Don’t Cry Workshops and our contribution to the Open Heritage Weekend – Naming of Parts and Graphs. Many of the volunteers seem very interested. Bryan is particularly supportive and both Sue and Helen said they would like to come on the Writing Workshop. Stella suggests that volunteers who hadn’t worked at the hospital could choose a story from the museums existing recordings for the Memory workshop. Ann says she will bring the hairdresser and there are a few others that she is still in touch with.

13th July

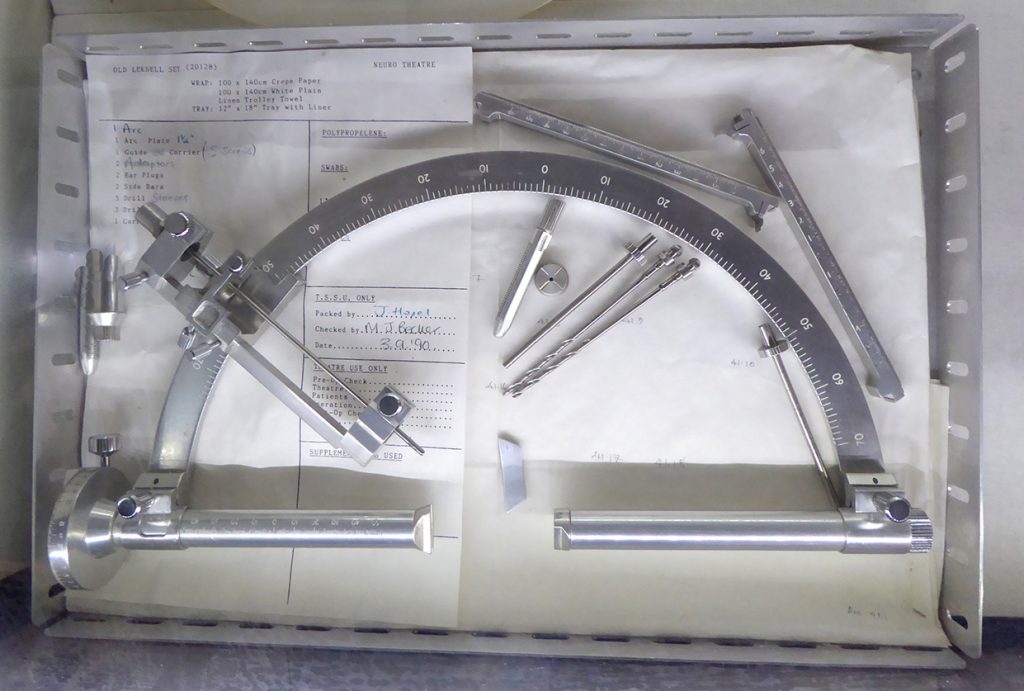

Pat and I continue the process of describing and reflecting on the cabinets in the museum. Today I find myself in front of a cabinet filled with a variety of chrome tools for operations, each adapted for a different task in the operating procedure, perfectly weighted and shaped for the grip of a hand. Next to it hangs a photograph of a team of doctors and nurses standing around an operating table, the patient lies hidden between them, below a pile of sheets. One of the doctors is holding a limb and half turns, his moustached lips smiling to the camera.

Excerpt from Sponge Holding Forceps

Sponge holding forceps

Intestine crushing clamp

Cheatles Sterilised forceps

R B Shears

Someone sat and designed

each object

here on display

for specific use

a pinch of fingers

the exact grasp of a hand

curve

hook

point

to

penetrate

investigate

clamp back

flay

remove

each tool perfectly devised

through practice

for its appropriate action

6th July

Encouraged by our presentation of Flight at the Language, Landscape and the Sublime conference, Pat and I start planning the Unlocked Writing Workshop. We write a list of exercises we want to introduce and try to estimate how long they will take. We decide to trial some of the exercises and time them. It’s interesting to see how the exercises change in the course of doing them, we want to question assumptions brought into the museum – I notice by the words I initially choose, my own assumptions are working overtime. We do the exercises again and decide to do a 15 minute piece of writing every time we are there. This will be the basis of a new piece of work – Touched – which like Flight will start as a performance reading with images and then possibly become something else.

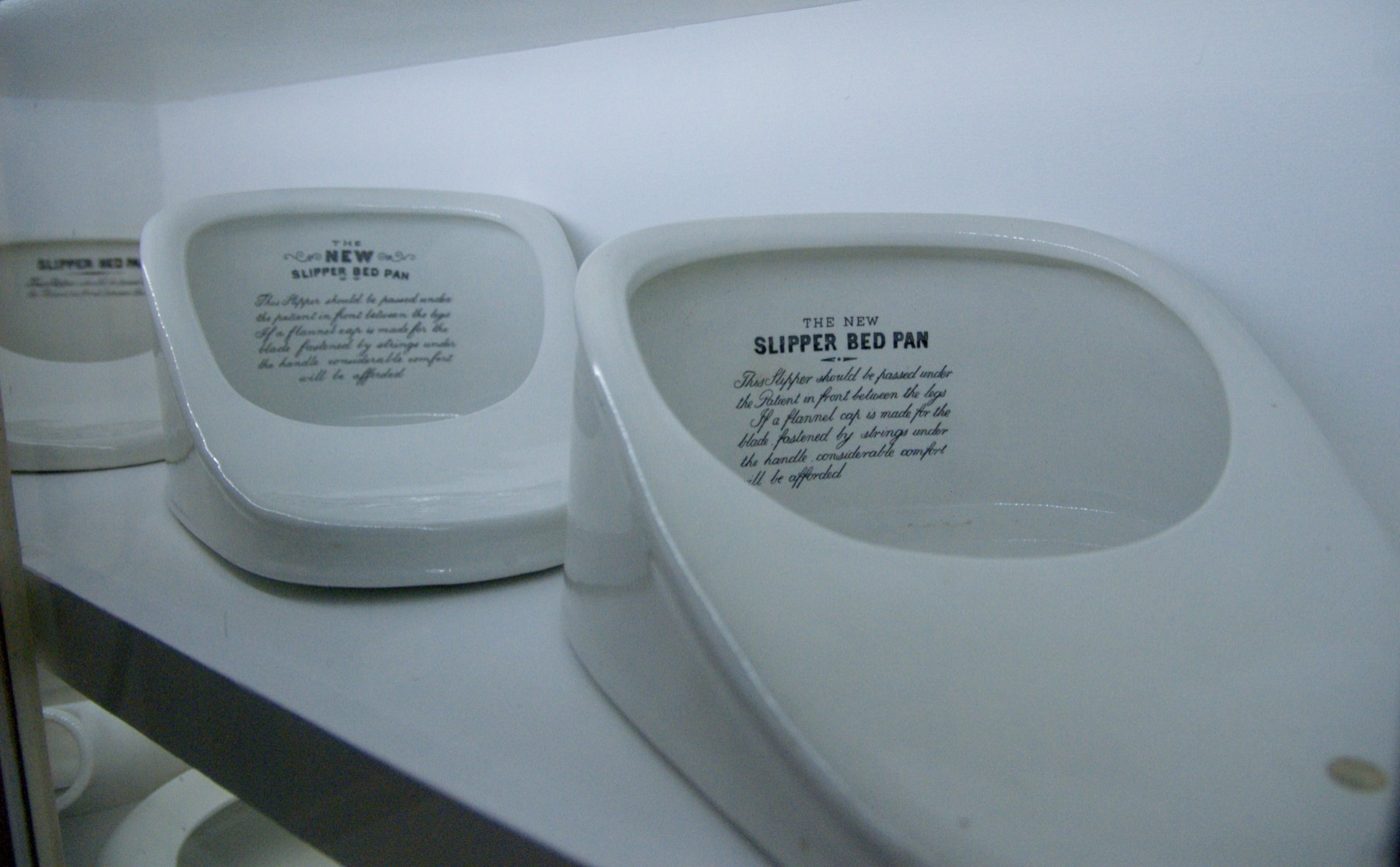

excerpt from This Slipper Bedpan:

This slipper bed pan

should be passed under

the patient in front

between the legs

If a flannel cap is made

for the blade

fastened by strings

under the handle

considerable comfort

will be

afforded

Nil by Mouth

When I first visited

she could get out of bed

in the row of beds

slowly

and with my help

carefully

walk

to the

bathroom to pass,

in brackets

(water)

My interest in the patients came from looking at a wonderful spreadsheet of all the admissions to the hospital between 1861 when it opened and 1900, over 5000 of them. Starting in 1894 photos were taken of patients on admission and the records include around 700 portraits. Looking at these people and reading the spare notes on them in the spreadsheet is truly moving. They are people just like us. They were working people, their lives were hard, some were desperate.

Paul Tobia did this research at the Bristol Archive, he studied all the medical notes and tabulated the information. Some of the portraits he found are now displayed in the museum.

Many of the patients were in states of extreme ill health when they were admitted, up to half of them died within the year. There are a number messages from medical superintendents (Doctor in charge of the hospital) to Bristol City Council complaining that patients are being sent to them in such poor states of health that they are beyond help.

At this time there were limited diagnoses available to doctors; Mania, Dementia or Melancholia were the principal ones, with just a smattering of imbecility and occasional others. Paul Tobia noticed that the different medical superintendents favoured different diagnoses. The first one, Dr Stephens, did not believe in dementia and most patients were labeled as suffering from mania, whereas Dr Thompson, who took over in 1871, was more liable to diagnose dementia than mania.

We may think that Victorian women did not work but many of the women patients have occupations given, domestic servant is the most common occupation, but there are some more exotic jobs recorded; governess, sextoness, weaver, shoe binder, ex-bawdyhouse keeper. These are not wealthy people, the notes confirm their hard lives, they are recorded as suffering from ‘ill treatment by husband’, starvation, ill health, business worries, overwork, grief. A surprisingly large number are stated to have epilepsy, also noted are those with ‘General Paralysis of the Insane’ which today we know as Syphilis, at that time it wasn’t known that this was a sexually transmitted disease or that there was no cure for it. It is seen more frequently in men, they people died in the hospital and usually quite soon.

Analysing the data in the spread sheet has become my project. I have made various graphs from it and have been thinking as to how to express these data in a more physical and more interesting way. Excel graphs have their points but they are inclined to be dull and a bit uniform. I want to express some of the emotion attached to this data – these peoples lives.

Becoming a volunteer at the Glenside Hospital Museum seemed to be a good way of getting ones thoughts around the Unlocked project; what the museum stands for and what it contains – the stuff, the memories, the implications. All huge, of course, as be expected of such an institution; the museum of the Bristol Lunatic Asylum.

A very interesting job was analysing visitor response questionnaires. One question was ‘What would you like more of?’ Frequently the answer would be ‘Patients’ stories’. There is Gertrude’s story in a display case, but no others and in many ways the lives and experiences of patients are absent from the museum. There are dioramas gruesome instruments and other medical equipment.

There are photographs of the interior of the building but they are very posed and mostly empty of people. Due to the necessity for confidentiality no patients may be shown or referred to without they or their families permission until the records are over 100 years old. Thus the patient experience is an absent presence in the museum.

Welcome to Unlocked.

We are so excited that our proposal for Unlocked to be undertaken as artists in residence at Glenside Hospital Museum has received funding from Bristol City Creative Seed Fund, and then from the Arts Council. We’ve been champing to get underway with the project all the time we’ve been writing!